ISKINDEREYA … LEH? (Alexandria … Why?, Egypt/Algeria 1979, 1.3., Introduction: Alia Ayman & 23.3.) This was the first of Chahine’s four-part autobiographical series, which created a unique universe based on memories, dream states, sensualities and cultural references. It is set in Chahine’s birthplace Alexandria during the Second World War as British and Egyptian troops were fighting the approaching Germans. At the center of the plot is the schoolboy Yehia (Chahine’s alter ego) who is passionate about Hollywood cinema and secretly dreams of becoming an actor. “I expressed my view as an Egyptian artist, my stance towards the societal, political and economic events of a time, during which the first decisive change of my life took place.” (Youssef Chahine, 1981). The film was awarded the Silver Bear at the 1979 Berlin film festival. It was Chahine’s first major award, 29 years into his career.

ISKINDEREYA KAMAN WA KAMAN (Alexandria Again and Forever, Egypt/F 1989, 2.3., Introduction: Marianne Khoury & 24.3.) The third part of Chahine’s tetralogy once again brings together parts of his own biography. This time he himself plays his alter ego Yehia, who is at the height of his career after winning the main award at the Berlinale (for ISKINDEREYA … LEH? 1979). His separation from a young actor however precipitates him into a personal and artistic crisis. During a hunger strike to protest against poor working conditions in Egypt’s film industry, he meets an aspiring actress. “In terms of style, the film is full of breaches and ‘rule violations’, committed only to the freedom of filmmaking.” (Filmdienst)

BAB AL-HADID (Cairo Station, Egypt 1958, 2.3., Introduction: Viola Shafik & 22.3.) A classic of world cinema whose unsparing depiction of poverty and human despair is timeless: Youssef Chahine plays the lame Qinawi, who lugs himself around Cairo’s main station selling newspapers. Shunned and lonely, he draws hope of escape from his misery from pin-ups on the walls of his room. He falls in passionate but desperate love, with the attractive cold drinks vendor (Hind Rostom) but she rejects him. He decides to commit suicide. “All the elements are firmly connected, the exciting crime story is organically linked to a memorable depiction of characters and their environment. The economy of the plot is reminiscent of the English and American school of crime film (Chahine admires Hitchcock) while neorealist influences are discernible in the treatment of the characters.” (Erika Richter)

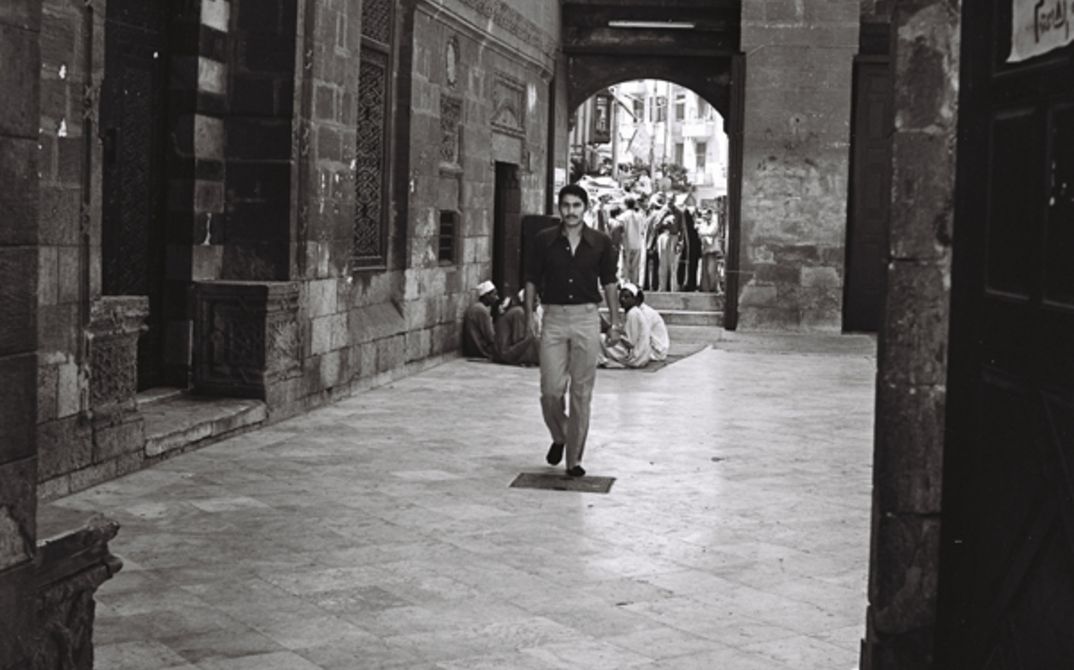

AL KAHERA MENAWARA BE AHLAHA (Cairo, As Seen by Chahine, Egypt/F 1991, 3. & 24.3.) Versed in all formats, Chahine made six shorts, some of them of a documentary nature, over his career. His penultimate was AL KAHERA MENAWARA BE AHLAHA, a breathtakingly dense and astute take on the classic symphony of a city. “I received a fax from France. They want a documentary about Cairo. What do you think they expect?” asks Chahine of his young listeners. This (self-)ironic introduction is followed by a loving, multi-faceted portrait of his city: Overpopulation and poverty on the one hand, family and sociability and secret caresses in a room lit only by the television on the other. “I love Cairo. So deeply, that when asked why, I am a loss for words.” says Chahine in French. “It’s people that I love, not stones.“ Life and love become cinema pictures.

AL ASFOUR (The Sparrow, Egypt 1972, 3.3., Introduction: Alia Ayman & 10.3., Lecture: Mathilde Rouxel) The first film to be made by Misr International must, alongside El Ikhetiyar (The Choice, 1970), which unfortunately is not currently available, be considered as Chahine’s boldest attempt at political cinema and should be judged as a central work in his oeuvre. A young police officer and a journalist try to free a village of corruption and misery. As if to illustrate the opaqueness of the exploitative structures, Chahine eschews traditional narrative structures, using flashbacks and associations to form a brilliant bridge between film noir and politically-committed “auteur” cinema of the 1960s and 70s. “After the 5th June [the beginning of the Six-Day War) a change took place: I went from making bourgeois cinema for entertainment to broaching certain themes within the framework of this cinema and then on to making films that corresponded to the real needs of society” (Youssef Chahine)

BABA AMIN (Daddy Amin, Egypt 1950, 4.3.) Amin, a good-natured, small-time employee, lives modestly with his wife and their two children. A friend convinces him to invest the family savings into an enterprise that will make them rich. Amin’s sudden disappearance plunges his family into despair. After his death, his ghost witnesses all the blows of fate that strike the family. Chanine’s directorial feature-length debut at the age of 24 (he became the youngest Egyptian film director in history) is almost an essence concocted from Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol”, Leo McCarey’s Good Sam and Egyptian musical comedy. This rarity is one of the films that would not have been available for adequate viewing without MIF’s restoration project.

SAYYIDAT AL-QITAR (Lady on a Train, Egypt 1953, 5. & 22.3.) Thanks to Ibn El Nil (Son of the Nile, 1951; currently not available) that followed BABA AMIN, Chahine was invited to the Cannes and Venice film festivals and won international acclaim. But he returned to the realm of popular Egyptian cinema to perfect his directing skills. SAYYIDAT AL-QITAR and its series of tragic events unique to classic melodrama tells the story of a singer named Fekreya married to a good-for-nothing addicted to gambling. He loses her money and then fakes her death in a train accident so that he can cash in on a life insurance policy and plans other misdeeds. Chahine played the lead role alongside singer and actress Leila Mourad who was one of the great stars of the Arab world at the time.

SERAA FIL WADI (The Blazing Sun, Egypt 1954, 6. & 29.3.) In pre-revolutionary Egypt, the young agronomist Ahmed (Omar Sharif in his first film role) dreams of improving the sugarcane harvesting conditions in his underdeveloped village. At the same time, he is in love with Amal (Faten Hamama), the daughter of a pasha, with whom he ends up conducting a bitter battle that culminates in a furious finale at the temple of Karnak. “Although this was one of the first films to have seriously problematized the situation of the rural population it can still be assigned to the category of adventure film.” (Viola Shafik) The film’s premiere at Cannes cemented Chahine’s reputation as an exceptionally talented maker of popular Egyptian cinema and launched Omar Sharif’s international career.

AL YOM AL-SADES (The Sixth Day, Egypt/F 1986, 9.3., Video-essay/Lecture: Mohamad El-Hadidi & 14.3.) An exhilarating, artistic adaptation of the French writer Andrée Chedid’s eponymous 1960 novel, which is set in Cairo in 1947 during a cholera epidemic. One infected man affirms that he will either succumb or be resuscitated on the sixth day. A washerwoman (played by Egyptian-born French singer Dalida) cares devotedly for her paralyzed husband and tries to prevent her beloved grandson from being infected. One day she encounters a young scoundrel who denounces people with cholera to the authorities but also has a great sensitivity for cinema and dreams. “An impressive film poem by the Egyptian old master Chahine, which explores the dreams of the protagonists as much as the questions of a world after the Deluge and creates a tale that is as sensual as it is didactic and educational.” (Filmdienst)

SERAA FIL MINA (Dark Waters, Egypt 1956, 9.3.) Another film starring the dream duo of 1950s Egyptian cinema, Omar Sharif und Faten Hamama: The sailor Ragab returns to his hometown Alexandria after three years at sea to marry his cousin Hamida. But he discovers that his childhood friend has taken a fancy to her. Chahine considered this film one of his most important of the period because it was the first time that he turned his attention to the working class.

AL NIL WAL HAYA (Once Upon a Time … The Nile, Egypt/USSR 1969, 11.3., Introduction: Gary Vanisian & 24.3.) This momentous 70mm project about the construction of Aswan High Dam was the first coproduction between the United Arab Republic (UAR) and the URRS. The version that Chahine completed in 1968 was rejected by both sides and only released much later on 35mm. “Conceived initially as a glorification of Egyptian-Soviet cooperation, whose symbol was the Aswan High Dam, under Chahine’s influence the film turned into a hymn to people, to friendship and sincerity.” (Magda Wassef) The artist Ala Younis dedicated the excellent two-channel video installation “High Dam” (2017, Forum Expanded 2018) to the eventful making of the film story. Using slides and posters, she gave an insight into the politics of the time and Chahine’s attempts to circumvent the censors. The installation will be presented to accompany the screenings of AL NIL WAL HAYA.

AL ARD (The Land, Egypt 1970, 12. & 29.3., Introduction: Maria Mohr) This adaptation of the famous 1954 epic novel by Abdel Rahman al-Sharqawi “The Earth” is set in the early 1930s, when feudal structures still existed in rural Egypt. It is a passionate portrait of the peasants in a village whose livelihoods are threatened when a new decree puts additional limits on their irrigation time. Only one peasant resists: Mohamed Abou Suwailam. The scene in which he, dripping with blood and sweat, works the land with his bare hands is one of the most remarkable in Egyptian cinema. This is also a central work in Chahine’s oeuvre and helped to solidify his reputation as one of the most important representatives of the realist cinema explicitly promoted by the Egyptian Film Organization for a brief period at the end of the 1960s.

HADOUTA MASRIYA (An Egyptian Story, Egypt 1982, 13. & 23.3.) The second part of Chahine’s Alexandria quartet whose title translates as “Egyptian fairy tale” begins with a disaster: Chahine’s alter ego, Yehia, is in London in 1973 when he has a heart attack and has to undergo emergency surgery. He sees his former life go by as he is being operated upon – with his ribcage transforming into a courtroom where he is tried for his errors. “The story corresponds to the one of Bob Fosse in All That Jazz (1979) and the questions that the artists asks of his own life while he is undergoing heart surgery are the same. But this time the filmmaker – in a very non-purist way – mixes real life with fiction, politics with the dream factory.” (Louis Marcorelles)

ISKINDEREYA … NEW YORK (Alexandria … New York, Egypt/F 2004, 13. & 25.3.) When he was 78, Chahine made the fourth and last part of his Alexandria tetralogy, bringing to a close one of the most innovative series of film history. After 40 years, the filmmaker Yehia meets his first love Ginger in New York and finds out that he has a son with her. “A stormy epic in which the heroes love, sing, dance, laugh and cry. A wonderful story about the difficulties of a man’s love for a woman and for America.” (Filmfest Hamburg, 2004)

AWDET AL-IBN AL-DAL (Return of the Prodigal Son, Egypt 1976, 14. & 31.3.) According to the major Egyptian poet Ahmed Fouad Negm, Chahine triggered a minor earthquake in Arab cinema with this film, the first in which he dared tell a story from his personal perspective. It was an adaptation of the eponymous 1907 novel by the French writer André Gide, who later won the Nobel Prize for literature. “The politicization of the biblical parable is not heavy-handed. Songs and dances from Arab culture combined with US-inspired music hall elements bestow upon the film the gripping freshness of an American comedy,” wrote French writer and critic Jean-Louis Bory. This too is one of Chahine’s works that deserves much more attention.

AL MOHAGER (The Emigrant, Egypt/F 1994, 17. & 26.3.) In his first film of the 1990s, Chahine went back in time 3,000 years, taking the biblical story of Joseph as a source of inspiration. His main protagonist Ram, who belongs to a poor tribe that lives on arid land, wants to change his life. He sets off on a long arduous journey to the Egypt of the pharaohs that he longs for. This melancholy, but militant work about the search for wisdom, told with grand and gracious imagery was released to huge success in the Egyptian cinemas. But it was soon banned after pressure from Islamist fundamentalists. Chahine appealed and won the case but then faced another ban after pressure from a Christian fundamentalist disturbed by the film’s deviations from the Old Testament.

AL MASSIR (Destiny, Egypt/F 1997, 18. & 27.3.) is another historical film which took the past to ask important questions about the present: It collects and illustrates scenes in formulaic takes from the life of the major 12th-century Islamic philosopher, judge and translator Ibn Rushd (also known as Averroës). He embodied a short-lived period of Islamic enlightenment at the end of the 12th century. After the caliph of Córdoba came under pressure from fundamentalists, he ordered the burning of his books and his banishment to Marrakesh.

AL NASSER SALAH AL-DIN (Saladin the Victorious, Egypt 1963, 19.3.) Funded by the legendary producer Assia Dagher and one of the most expensive Egyptian films ever, this is a pan-Arab historical epic about the sultan Saladin (1138 - 1193), who built a united Arab front against Christian crusaders. “At the time, ‘Saladin’ was proclaimed everywhere as a film that glorified Nasser and Arab unity. Nobody listened to me when I insisted that it was above all a tribute to tolerance. By combining extracts from the Quran with hymns about the birth of Jesus, I wanted to commemorate the gesture of the Sultan of Syria and Egypt, when he announced a truce so that the besieged crusaders could celebrate Christmas mass. Is that not lovely?” (Youssef Chahine)

FAGR YOM GUEDID (Dawn of a New Day, Egypt 1964, 21. & 30.3.) Yet another undervalued work which is an example of Chahine’s sense for human sensibilities in the mirror of contemporary societal and political developments and captures the urges and vibes of its time on the screen. It is the story of a 40-year-old married woman who has fallen into idleness and does not know how to approach the revolutionary events in her country. She finds a new meaning in life when she falls in love with an aspiring young student. “I shot FAGR YOM GUEDID in 1964. I count it among my best films and still stand by it completely. It is about the class whose assets were nationalized after the 1952 revolution. I explored the question of whether this class still had a place in Egyptian society.” (Youssef Chahine)

HEYA FAWDA (Chaos, Youssef Chahine, Khaled Youssef, Egypt/F 2007, 30.3.) Chahine co-directed his last film with Khaled Youssef, who had also worked on some of the screenplays of earlier works. The film is set largely in Cairo’s Shoubra district, once known for people of different religions living in peaceful coexistence, but now rife with social and political tensions. It is run by a corrupt police officer who is hated by all the locals. Only the woman with whom he is in love resists him. With visionary clarity, Chahine and Youseff develop a panorama of a people’s outbreak of anger in a violent police state, which seems to anticipate the revolution of 2011. Chahine’s conclusion of a unique directorial career is evidence that he was an incorrigible advocate of humanity. (gv)

The program will be accompanied by a discussion in English about the contemporary pertinence of Youssef Chahine’s cinema, with Alia Ayman, Marianne Khoury, Viola Shafik, Mohamad El-Hadidi und Mohammad Shawky Hassan. (3.3.)

There will also be a publication about Chahine, comprising texts by Alia Ayman, Yasmin Desouki, Nour El Safoury and Mohamad El-Hadidi, to accompany Arsenal’s retrospective. Thanks to the Cinémathèque française

Organized in cooperation with Misr International Films (MIF). Thank you to Marianne Khoury, Gabriel Khoury, Nawara Shoukry and Ahmed Sobky. This retrospective is part of the “Archive außer sich” project.