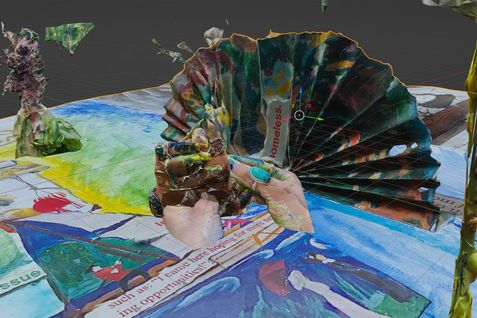

The 20th edition of Forum Expanded presents cinematic works from 21 countries at the Forum Expanded cinemas, the silent green Betonhalle, and the Marshall McLuhan Salon of the Embassy of Canada . Employing practices that span installation, film, video and sculpture, the selected artists and filmmakers employ translucence as a means of engaging with the cataclysmic realities of the present.

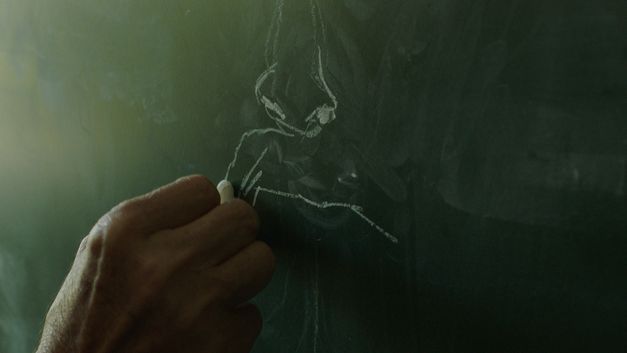

Whether dealing with personal or collective histories, ongoing wars, extractivism, legacies of colonialism or social inequalities, the artists’ approaches frequently hinge on intervention rather than observation. Be it through tinted glass, virtual reality, historical speculation or sonic augmentation: their works actively project ideas, images and sounds that alter how we perceive reality and refract our view of the world. They make what is missing even more tangible by redirecting our gaze and throw what lies beyond or outside of our perception into ever sharper relief as a result.