Japanese artist and filmmaker Takahiko Iimura—who passed away recently on 31 July 2022 in Tokyo at the age of 85—was a leading figure in Japanese experimental film and media. He will remain significant in Japanese art and film history as a pioneering figure in experimental film, video art, expanded cinema, and moving image installations. What’s often neglected in writings on his life, however, is that he was a perennial explorer not just of different media but also the world, travelling around for much of his lifetime.

Especially in his youth in the mid-1960s to mid-1970s, Iimura, often accompanied by his wife Akiko—who outlives Iimura and is a writer, translator, and artist in her own right—went from country to country armed with film prints of works by him and by his peers. Living in Tokyo and New York for most of his life, Iimura is widely recognized for his contributions to the American avant-garde. Works like FILMMAKERS (1966–69), NEW YORK SCENE (1966), and SUMMER HAPPENINGS U.S.A. (1967–68) demonstrate Iimura’s thirst for new experiences and encounters and his ability to absorb and channel his experiences into his artistic practice. In other words, he travelled not only to exhibit but also to be inspired.

“No matter where you travel, there is always the here and now [...] No matter where you go, the screen is always white.”1Takahiko Iimura: “Paris – Tokyo eiga nikki” (Paris-Tokyo Film Diary), Tokyo: Seiunsha, 1985, p. 92. Takahiko Iimura

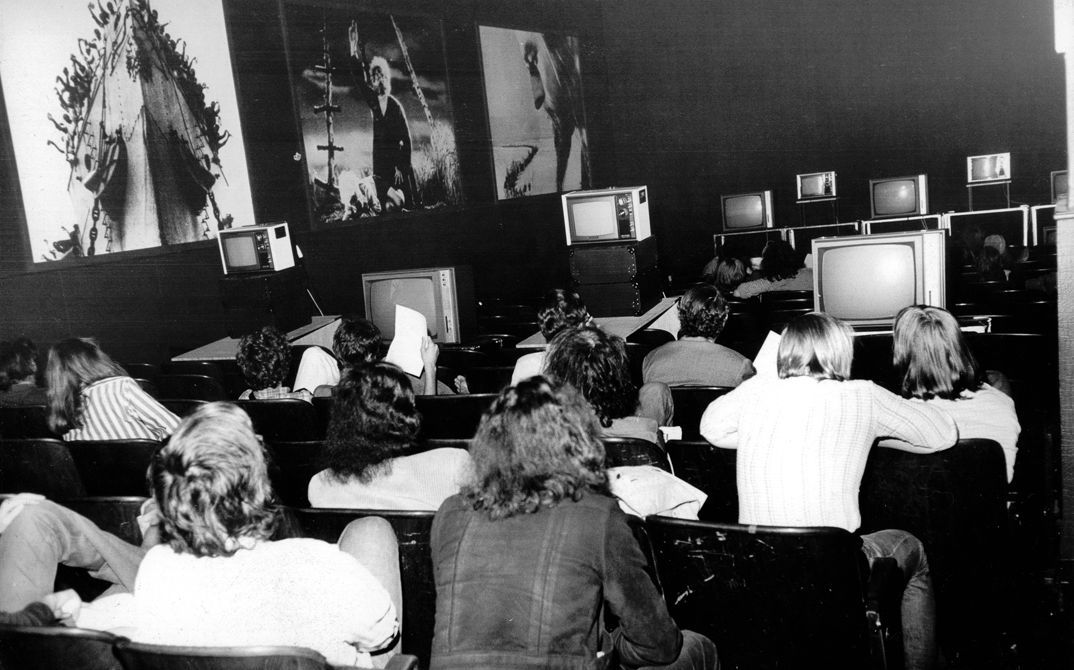

While New York remained his second home for life, this essay seeks to address his travel across and stay within Europe, with a particular focus on his stay in Berlin2Iimura also frequently mentioned teaching at what he calls “Schiller College” during that time as a visiting scholar. What he taught and which institution specifically he was referring to could not be verified. Schiller International University did exist at the time, but this school is located in Heidelberg in what was then West-Germany, so a regular teaching engagement while based in West-Berlin seems unlikely. between 1973–74 on a DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program fellowship.3During his DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program fellowship in 1973, Iimura exhibited at the following institutions across Germany: America Haus, Berlin, in March, where he exhibited his films as part of the group presentation “Environmental Structures”; Arsenal, Berlin, where he presented film and video works over a five-day presentation “Avantgarde aus Japan”; XScreen, Cologne, in May with the solo screening “Neue Filme von Taka Iimura”; Abaton-Kino, Hamburg, in June as part of the group presentation “Hamburger Filmschau 1973”; Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, in August, with the solo presentation “Taka Iimura, Filme + Video Tapes”; Akademie der Künste, Berlin, in September – October as part of the group exhibition “Aktionen der Avantgarde”; Galerie Paramedia, Berlin, in November as part of the solo exhibition “Film On Paper”; and, once again, at Arsenal, Berlin, with the solo screening “Filme von Taka Iimura.” His time in Berlin was preceded by a six-month screening tour around Europe in 1969—where he visited the German cities Düsseldorf, Oberhausen, Cologne, Kassel, Munich, Frankfurt, and Berlin—an experience which he clearly cherished, bringing him back several years later for a longer stay.4Iimura presented his films in 1969 at Experiment in Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen (26 March), XScreen, Cologne (10 April), Freunde der Deutschen Kinemathek, Berlin (20–21 May), Hochschule für Bildende Künste Kassel (23 May), Augusta-Kino, Munich (30–31 May), and at the film festival Experimenta ‘69 in Cantatesaal, Frankfurt (4 June). With Berlin as his base, Iimura participated in many exhibitions and screenings throughout the European continent, until eventually relocating to Paris in 1974 where he lived for another year before returning to Tokyo.5Iimura exhibited work at the following institutions outside of Germany during his DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program fellowship: Musée du cinéma (Brussels); Palais Thurn und Taxis (Bregenz, Austria, July 1973); Theater am Landhausplatz (Innsbruck, Austria, July 1973); the National Film Theatre (London, September 1973, as part of the Independent Avantgarde Film Festival); and Milkweg (Amsterdam, November 1973) during his time in Berlin. While his stay was temporary, I’d like to propose his lived experience and living situations in Europe during this period shaped his artistic practice in film and video in a transitional moment of his career.

Film on Paper: Iimura’s Storyboards

The local context and situations Iimura found himself in Europe—between 1973–74 in Berlin and 1974 in Paris—shaped his artistic activities in several ways. Although he expressed a desire to shoot films in this period, his access to film equipment was limited and he discovered that buying film was significantly more expensive in Europe compared to the US or Japan. In a 1971 letter exchange with the Artists-in-Berlin Program, Iimura’s request to be considered for the fellowship was initially rejected on the grounds that there was a lack of technical facilities for filmmaking, to which Iimura replied he would bring his own equipment as his practice has always been small in scale.6The DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program kindly shared their archival materials, including letter exchanges with Takahiko Iimura in this period, to Arsenal and I was able to reference them for this article. In the end, he resorted to drawing what could be described as a “storyboard”, or compositions of black and clear frames, on a type of Japanese-style paper usually intended for handwritten manuscripts, which has small squares printed on it for each individual Japanese character. Approximating the frames of a filmstrip, Iimura discovered that this paper was useful for him to develop concepts even with meagre means. With the Berlin-based small press Edition Hundertmark, Iimura produced limited-run publications of a thirteen-page film storyboard “1 to 100” (1973) and contributed to their “10 Year Box” (1973), a publication celebrating their ten-year anniversary, with the video score for SELF IDENTITY, the former of which he exhibited as part of his solo exhibition “Film on Paper” at Galerie Paramedia, Berlin, the same year. Iimura received more invitations in Europe to present his works on video than film, as video works were still a rarity in the continent at the time compared to the United States. These conditions led him to temporarily abandon shooting on analogue film and pursue experimentation in film installation, for which he mainly utilized the relatively inexpensive black and clear film leader, as well as video performance and video installation, for which he primarily implemented the live-feed function.