II. 1971: A Body of Work

The selection made by the 1971 programming team not only accurately reflects the variety of visual approaches employed by the Third Cinema, but also the diversity of its forms of collaborative organisation and the breadth of its stylistic spectrum, with the entire programme bearing witness to this.

Three of the films came directly from the Etats généraux, thanks to the ceaseless work of Chris Marker. Les mots on un sens is the name of the Paris episode of the series On vous parle de, whose opening credits announce its inspiration to function as a sort of anti-TV news broadcast. In addition to episodes devoted, for example, to torture in Brazil or the assassination of communist leader Carlos Marighella, the broadcast dedicated to François Maspero helped demonstrate the show's ability to combine theory and practice and paid tribute to the work of a broadcaster with internationalist ideals who fought on all fronts, whether political, societal or artistic. Maspero's non-dogmatic Marxist stance resonates with that of the programming choices made in 1971.

Slon/ISKRA, the same production company that made Les mots ont un sens, Sochaux 11 juin 68 and Les trois-quarts de la vie, gave rise to one of the most remarkable collaborative initiatives in history: the Medvedkin Groups. This involved workers being trained to operate cinematographic equipment by some of the greatest filmmakers and technicians of the time, thus enabling them to describe the conditions in which they lived and the struggles they underwent in their own words. As Henri Traforetti, one of the young workers at the company Rhodiacéta, described his experiences to this end: “Section 4 of the Medvedkin Group's statutes states: ‘We wish to give the working class new possibilities of expression through photography, film and sound in order to depict all aspects of the working class condition, from alienation to activism, and we hope to establish a new way of educating and training activists.’ These films counter-attack by providing counter-information: they are veritable battle cries, calls for revolt whose sheer force is undeniable, calling for the action needed for the individual to be seen as a human being and not a commodity. This cinematographic and human experience, in which I participated and to which I made a small contribution, was a great moment. It changed the course of our lives, of my life.” (March 5, 2013 Conference, Besançon).

In addition to these exceptional experiments in film and life, El cuarto poder and Phela-ndaba (End of the Dialogue) stand out for being as urgent as they are fearless: they were made under two dictatorships and, as with the Ciné Liberación group in Argentina, the filmmakers risked their freedom and even their lives to make them.

The result of a meeting between film students Antonia Caccia and Simon Louvish and activists from the Pan-African Congress living in exile in London, Phela-ndaba (End of Dialogue) offers an unflinching account of apartheid in South Africa. The contrasting structure of the film, which alternates between colour and black & white, statistics and silence, words and music, culminates in a moving tribute to the activists executed by the racist regime in Pretoria and is a testament to the film's mastery of style. Producer Nana Mahomo explains the meaning of the title: “African nationalism wasted its time declaring that white and black South Africans should be equal citizens of the same country. We wanted to be good citizens, to raise our children decently, to lead a white kind of life and all that nonsense. Back then we still believed in dialogue. Now that's over. What we face now is how to prepare a military response to the ongoing aggression that is apartheid.” (Taken from “Guide des films anti-impérialistes”, by Guy Hennebelle, 1975).

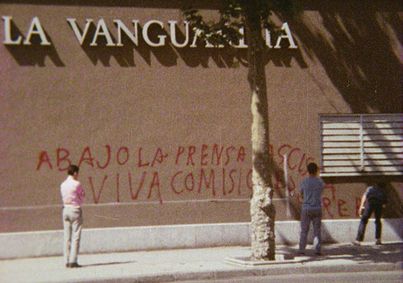

Made by the Colectivo Cine de Clase, which both protected the filmmakers and allowed them to express their political views, El cuarto poder is an analysis of disinformation and a plea for the formation of a clandestine press run by the people. It is the result of the bravery of two people, a couple: Helena Lumbreras and Mariano Lisa. Mariano describes the career of Helena, who passed away in 1995 as such:

“She was a European filmmaker trained at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia of Cinecittà in Rome. She worked in Italian cinema and TV (RAI) and also devoted herself to activist cinema, following in the footsteps of the alternative movement that developed in France, as well as working in collaboration with filmmakers such as Chris Marker.

Helena Lumbreras directed films that were edgy, critical, socially committed and aesthetically rigorous films which she shot in extreme secrecy, risking her own life. She suffered first-hand while imprisoned under Franco's dictatorship. As a woman, Helena encountered enormous obstacles and great hostility, not only from the state apparatus, but even from beyond the dictatorship and its backwards mentality from the political apparatuses of left-wing parties, which tried to dismiss her as a filmmaker entirely. Even today, Helena has remained invisible in her country for the unspeakable, yet very real reason of rampant machismo and authoritarianism. Her work remains not in the hell of punishment as if condemned, but rather suspended in the limbo of ignorance.” (personal letter, December 23, 2011).

Helena Lumbreras could have been one of the women filmed by Louise Alaimo, Judith Smith and Ellen Sorrin, the three directors of The Woman's Film. Although they worked as a group and as part of the broad cooperative movement called the Newsreel collective (created with the encouragement of Jonas Mekas), these three women have every reason to include their names as the directors. Lumbreras is essentially the European counterpart to one of the protagonists of The Woman's Film; she, like Lumbreras, is openly communist and lives subject to oppression in an anti-communist country. If El cuarto poder observes the political effects of ideology at a general level, The Woman's Film recounts the lived testimony of working class women who are victims of dual exploitation: that relating to their paid labour and that relating to their private lives (that is, their unpaid labour). Helena Lumbreras, Louise Alaimo, Judith Smith, Ellen Sorrin and their contemporaries agree on this point: “Their problems are caused not by personal shortcomings or relational difficulties, but by the very structure of capitalist society.” (Amos Vogel, “Film as A Subversive Art”, 1974).