One of the directors whose film we’re showing in this year’s programme wrote to us that she’d often been told by festivals that feminist themes are a niche concern and of limited interest for large audiences. You showed two very formally and thematically unusual feminist films at the Berlinale Forum (The Drifter, Forum 2010 and Top Girl or La déformation professionelle, Forum 2014). What role did being at the festival play for you?

That’s an interesting question and also one that makes it hard for me to take a position on the current debate surrounding the Berlinale, because the festival has had such a vital effect on my film career. It makes a huge difference for a film whether it’s shown at a big festival or not. Then there is press coverage or sales interest, for example.

And additional festival invitations then follow?

Yes, the visibility offered by a big festival is hugely important. The Drifter travelled the whole world, I wasn’t always there to see it, but the film was really everywhere, India, Canada, Israel, Cannes. But there’s also a lot of attention generated once the film has finished making the rounds at festivals, such as at universities, where people then write about the film. The academic scene in the US is actually discovering the film right now, I’ve been receiving lots of enquiries about showing it at seminars or symposiums. And all of this wouldn’t be happening if the film hadn’t received such visibility before.

Have you also been confronted with the view that feminism is a niche concern?

Of course. The more feminist or experimental a film is, the less likely it is that the big festivals will show it or if they do, it will only screen in a small sidebar. You usually get put in some sort of thematic programme called “film nouveau” or whatever.

But despite that, I would say that it’s not just to do with whether a film is feminist or not. There are lots of films labelled as such which simply have female characters or female heroes, which hardly makes them feminist films. Quite the contrary actually if we take, say, Wonder Woman as an example here.

Films with a strong female presence, on subjects with a female connotation or that explore femininity in general simply don’t receive the same attention. And when they show things from a feminist perspective to boot…

The studies available to us now via Pro Quote Film show exactly the same thing. It’s very easy to prove. But then you have to ask why it’s like that. The films themselves are really interesting and I think they’re just as interesting for audiences as well. That’s why it’s so important to analyse why this is the case. It’s only then that suitable countermeasures can be developed.

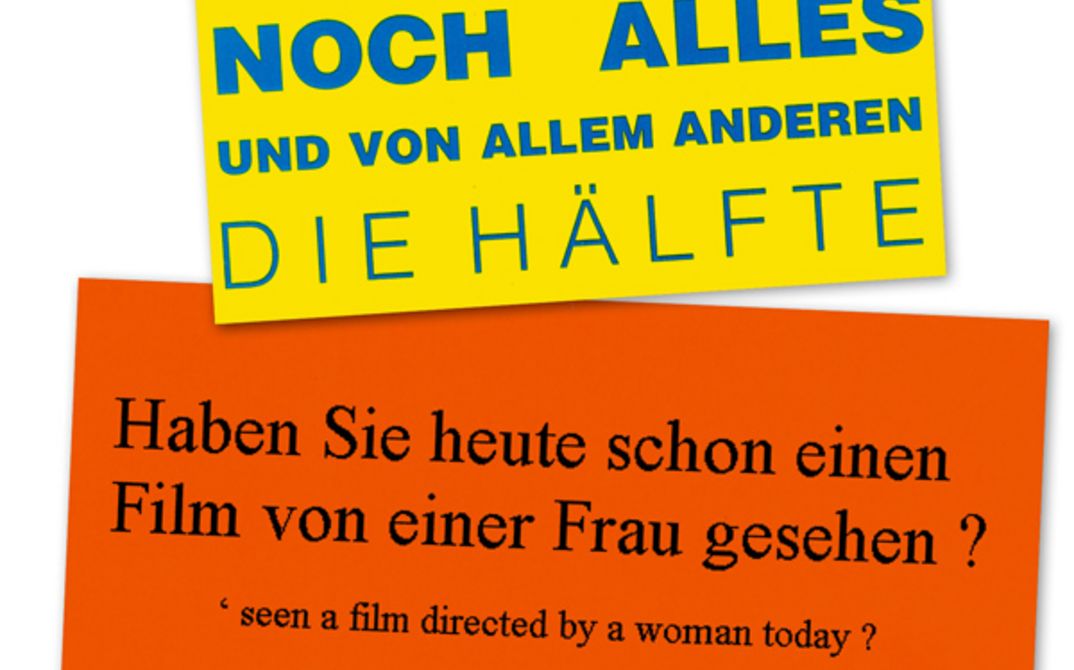

The Association of Female Film Workers used to hand out flyers at the Berlinale that said “Have you seen a film by a woman yet today?” The question of what proportion of female filmmakers are included in the programme is a question that still needs to be asked today. As a filmmaker, you’re involved with the Pro Quote Film initiative. What expectations do you have of festivals?

We have the same expectations in relation to festivals that we have in all other areas. In addition to quotas, we also demand, for example, that budgeting is awarded based on gender. Equal rights need to be a central concern from the very outset, not just a source of fuss and bother or some marginal contradiction. We have to bring out about a cultural shift, be clear about stereotyping and racist and sexist clichés. Festival directors must be more aware of what they’re showing and what they’re not showing, of what they and therefore their audiences too are missing out on. And alongside ushering in this cultural shift, we also demand equal representation in selection committees and juries. Although we also have to hope here that women stand up for women, for gender bias is deeply anchored in the minds of many women as well. Perhaps one can’t expect too much as a result, but it would be a good start in making the necessary cultural shift.

In this context, it’s important that we see a close connection between labour disputes and cultural shifts, which are two pillars mutually dependent on one another. And labour disputes are always also about money and participation.

It’s about getting the same amount of money, the same amount of visibility, and also the same amount of fame. And as far as bringing about a cultural shift is concerned, it’s about revealing stereotypes and changing the very visual language used in film. It’s not just that there’s a lack of stories both by women and about them, there’s also a lack of female perspectives, also female perspectives on men, and many types of female bodies are simply invisible. And if women received half of all the funding allocated for budgets, the whole culture would successively change in lasting fashion, regardless of gender bias. That’s why it’s not just about how visible women are on the big screen, it’s equally about changing the conditions for visibility.

I’m less able to judge what it’s like in the festival sector, but in the television sector, for example, women over 50, that is, experts, are invisible. Their opinion doesn’t count.

This is something we also discuss a great deal. It begins with how selection committees or juries are put together and obviously ends with what we actually select and show. But as a festival, we’re clearly not at the start of the food chain, the structural inequality begins further upstream, as it were, and relates to money. It goes without saying that we only see the films that actually get made, not the ones never able to made in the first place.

There’s already an imbalance in terms of the number of films submitted by men and the number submitted by women; as far as the films we’ve selected for the Forum and for Forum Expanded are concerned, the proportion of female directors is at least higher than it is when you look at submissions. Yet we’re still not entirely able to right this imbalance.

The next question is obviously what happens after the festival, which films find distribution, which films get bought.

Yes, indeed. Festivals also have profiles that they seek to uphold. The Forum is all about a diversity of cinematic languages, innovative perspectives – it’s to be expected that feminist films will show there. But you’re also some way from the mainstream. I wish there were also more female perspectives in the big competitions. The competition programmes of the most important international festivals often don’t contain a single female director. I find that such a shame, primarily for the audiences that don’t get to see so many great films as a result. Feminism has to enter the mainstream!

But it’s usually the case that the bigger the film, or rather the bigger the budget, the smaller the proportion of women involved.

That’s true. That’s what determines everything and that’s why it’s so necessary to keep pointing out that the idea of what a film is and the fantasies linked to it have to change. Director Helke Sander said forty years ago now that “mainstream equals malestream” and that could have changed in the meantime, but it hasn’t, despite there being a large number of women who actually decide what makes up the mainstream. But they clearly decide against their own. It’s depressing that there is so little critical awareness in such positions that women actually decide against their own just for a bit of power – if I may be a bit provocative here.

Within the context of #metoo and #timesup, being openly in favour of feminism or expressing solidarity with women suddenly seems “cool” at the moment and no longer carries a stigma. Can we therefore hope that this current wave of support may help to change the structural disadvantages faced by women in the film industry?

Yes, we’re obviously hoping for that, that’s why we founded Pro Quote Film in the first place. Now all professions and not just directors are supposed to bring this subject to the film industry in more wide-ranging and profound fashion. That will also certainly happen, although it goes without saying that it’s ultimately about the question of who decides. To be honest, the more I engage with the film and television industry, the more I notice that it’s like a bad dream for me as a female filmmaker. And in the end, I just have to hope that a lot is going to change. But there also has to be a political will for that to happen.

And right now, the question is where everything is headed. For that reason, one can now be very blatant in saying to all the left-wing, progressive filmmakers, directors and lecturers, and I’m specifically referring to the men among them here, that if they’re against gender equality, they’re quickly on the wrong side of things. Sexism, racism and classism have always been closely linked. And we shouldn’t forget that the wind is currently blowing in a strongly right-wing direction, against diversity, against making sexism visible, there are some very strong racist undercurrents. I wish that that people would take clearer stances, that more would happen in that respect, that the fear of losing something weren’t as big. I wish we could work together to make sure that diversity isn’t something that can suddenly just disappear again.

Do you experience solidarity from men and what form does it take?

Yes, of course, there’s solidarity. Our petitions are signed, we receive support, we’re asked to take part in discussions. But we also hear dissenting voices again and again. The whole subject is really multi-layered and that’s why we distinguish between the concepts of labour disputes and cultural shifts. We obviously can’t change state-owned television from one day to the next, which unfortunately also has a major effect on German cinema. For that reason, it’s irrelevant to us for the time being if a female director wants to adapt a Rosamunde Pilcher novel or not, that’s not what we’re interested in whatsoever. It’s ultimately about being able to work at all. But at the same time, we want the women who change gender images and gender roles to be able to use other forms of narration too.

And we also have to juggle these contradictions (women who produce films that contain conventional images of women). I expect my colleagues to recognise this balancing act and to realise that we obviously want a whole lot more than just for women to feel good about themselves within the system. The whole system is toxic and that’s what we have to change, we can only do that together.

Talking of solidarity: filmmaker Christoph Hochhäusler recently rejected the idea of quotas on his blog “parallelfilm” and criticised them as a being an ideological instrument.

Many people working in culture reject quotas and ultimately say that quality will out. But quality is itself a concept linked to power. What sort of quality are we taking about in each case and who defines it, who carries the power of definition? I think it’s a shame that this idea of cultural supremacy ultimately has a male connotation. Although I’d like to be very cautious here too, perhaps it’s more of a conservative cultural supremacy, let’s forget about the male connotation here. But as I said already, it’s ultimately about picking which side you want to be on.

We see films from the whole world which make clear just how different working conditions can be in a global context compared to Germany, where there are already big differences. Such discussions often remain tied to their immediate surroundings, in this case, Germany.

The discussion is elitist above all, that’s what’s German about it. The whole cultural crowd is hugely elitist. And that’s something you also have to grapple with. I’ve come across people in the film and television industry, and I’m explicitly not referring to Christoph Hochhäusler here, who are incredibly elitist and bigoted. And I’m really shocked how bigoted they are in clinging on to their fantasies of what an audience wants and in taking decisions accordingly. It’s outrageous and Pro Quote Film ultimately also stands for removing the hierarchy from this whole system. And in this context, the question also arises as to who has the prerogative of interpretation as far as film is concerned. Who possesses this prerogative? That’s a very important point. If we want emancipation, or even for emancipatory thought to be taken seriously at all, then these hierarchies, these elites, and this bigotry must simply be dismantled.

When opponents of quotas argue based on the idea that quality will out, they ignore in the process the role played by learning, working and gaining experience, for which one needs both money and opportunity in the film industry.

Do you see a contradiction in both discussing films and one’s own stance? Or do you sometimes see a forced originality in the sort of stance where you can’t permit yourself to say, yes, it’s perhaps not the optimal instrument, but I support it anyway?

They are the optimal instrument! Our hashtag won’t be #outcry or #metoo. We demand that they become law. That’s very important and decisive. And it’s great to have a law because that means you then have a legal entitlement. Quotas may not sound very attractive, but they are law. And for that, you require a majority. We work very politically. It’s therefore only a question of time until such a law arrives and is passed. And quotas make all sort of things happen much quicker. Once such a law is established, no one will be asking why there are now more women in the Competition. That will be just how it is.

Thank you for the discussion!

(The interview was conducted by Anna Hoffmann and Hanna Keller)