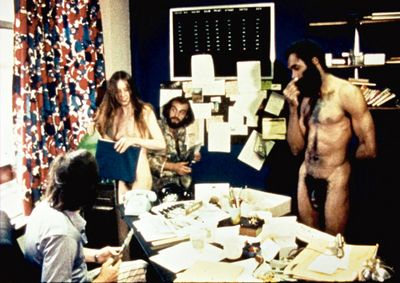

The sexual projects of the counterculture are thus framed between two different forms of the grotesque, though neither of them are narrated without hope. The country folk of Pennsylvania have fond memories of the eccentric doctor and mystic who lived in their midst. Companions, Reich’s widow and biographer Myron Sharaf are all equally enthusiastic, even when old footage bears witness to Reich calling for the election of Eisenhower and denouncing communism. Even the way in which the sexual history of communism, including clips of Stalin in propaganda films, is transposed to the tricky love affair between a Yugoslavian revolutionary and a Leninist ice dancer has reconciliatory components. It’s more the New York counterculture whose actions mostly seem fusty and absurd, even if they do occasionally come across as charming too. Tuli Kupferberg, poet, performer and co-founder of beatnik-rock cabaret The Fugs, gets dressed up as a soldier or armed street theatre performer and stomps around the neighbourhood while “Kill For Peace”, one of his band’s hits, plays. “Screw” editor Jim Buckley has his erect member cast in plaster by one of the female activists of the para-groupie Plaster Caster Foundation (an organisation that normally restricted itself to creating casts of rock star penises). To the viewer of today, this somehow seems further away than Wilhelm Reich and the sexual contradictions of socialism.

In combining the socialist sexual-political century with counterculture, Times Square and the dismantling of the Austrian psychoanalyst’s less orthodox interpretations of psychoanalysis on American farms, Makavejev succeeds in achieving an equilibrium between an almost melancholy, yet still spirited admiration for the waning sexual-revolutionary and Freudian-Marxist strands of socialism on the one hand and a sarcastic snicker at its grotesque concept fetishisms, behavioural models and esoteric dead ends on the other. The exemplary sublimation of figure skating, Eastern Europe’s discipline par excellence, forges links to the camp moments in the USA, such as when Jackie Curtis prays to the Madonna. It was only the potentially reactionary dimension of the American libertarians, who do in fact overlap in many ways with today’s new right, that Makavejev could not see, although it is there on screen regardless – for the images from New York seem nearly as fictional and dated as the Leninist Ice Prince. The Yugoslavian joke on the subject of dick sizes, on the other hand – “Don’t trust the media” – has something timeless about it. What’s more, this datedness is itself at once theme and method here, whereby today’s viewers feel just as trapped between different strata and sediments as did their contemporaries in 1971, despite the short appearances of the queer New York of the 1960s. Even its revival a few years back is already a long time ago now.

Diedrich Diederichsen writes essays on music, cinema, theatre, art and politics. He is a professor of the theory, practice and communication of contemporary art at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and publishes regularly in periodicals and newspapers.